Ā Te Taitokerau urutau i ngā āhuarangi

Responding to a changing climate in

Te Taitokerau/Northland

PHOTO: Ngātiwai kuia Bella Thompson shares stories of loss – and determination to hold on to local stories and mātauranga – with Commission visitors at Tuparehuia (Bland Bay). Photo / Whangarei District Council.

This is a story based on kōrero across Te Taitokerau/Northland in March 2025.

It reflects a visit by a team from He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission, to build our understanding of how climate change is experienced in different places and how people are responding.

These local case studies are key inputs in our independent advice to government on what is needed to address climate risks and support adaptation across the country.

People we talked to were keen for the stories to be shared to support other communities building their response.

Read more about the Commission and why we do case studies.

From the Chief Executive

When our team from He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission visited Te Taitokerau/Northland, our aim was to get a better understanding of how climate change is affecting the region, and what people are doing in response. That local experience is valuable for others around the motu and is a key input for our advice to government on adaptation.

This is a summary of what we saw and heard on our visit. It reports the climate change reality people are dealing with, the innovative responses they are making, and their view of what is needed from central government to effectively support local efforts.

Our thanks to everyone who hosted and talked with us: hapū and iwi, farmers and growers, businesses, community organisations, councils and the economic agency.

Jo Hendy, Chief Executive

The full case study report is published on our website.

Tēnā koutou katoa.

Ko te wehi ki te Kaihanga.

Ko te whakahōnore ki Te Arikinui Kuini Nga wai hono i te po. Pai mārire ki te Kāhui Ariki whānui tonu.

Poroporoākītia ngā mate huhua kei runga i a tātou katoa.

E kore e ārikarika ā mātou kō He Pou a Rangi mihi ki a koutou ko mana whenua, rātou ko hapori, ko umanga, ko kaunihera. Nō mātou kē te hōnore i te rongo i ā koutou nei kōrerorero me ngā toro i ā koutou wheako whaiaro i ngā urutau mō ngā āhua o Rangi.

Kua rongo, kua kite mātou i ngā whiwhinga ka riro i a koutou me te mahi ngātahi ā hapori, ā whaitua, ā rohe, ā motu hoki. Arā, ki te whakamanahia a mana whenua me te hāpori i ā rātou ake urutau, ka tutuki. Inā kē te tauira, ki te kotahi te kākaho ka whati, ki te kāpuia e kore e whati.

Me tā mātou tūmanako, ka kitea koutou e koutou anō i ngā whārangi ki raro nei hei tauira mā

Te Taitokerau, mā te motu. Anei anō te mihi.

The value of a close-up view

He Pou a Rangi Climate Change Commission uses case studies in our work on adaptation. They are central to our research approach – so we can better understand how climate change affects Aotearoa New Zealand at the local level, and how communities are responding.

The insights that communities share with us are useful to others working in adaptation in central and local government, business, hapori/communities and beyond. Many of the people we talked to in Te Taitokerau/Northland hoped their experience could be helpful to other regions.

Hearing directly from people on the ground is particularly important for adaptation, which is – in its very nature – local.

Case studies reveal common themes, and sometimes important differences, for a particular area or group. The shared elements and the distinctions form a picture of the effects of climate change across the country – and help reveal what central government action is needed to support communities and businesses with adaptation.

This is one of four case studies we have made between 2023 and 2025: the others are about Wairoa, South Dunedin and Westport.

The case studies will inform the second national climate change risk assessment, and our second monitoring report on progress on the Government’s national adaptation plan – both due in 2026. Those reports will combine local insights from our case studies with a wide range of other evidence to develop our formal assessments.

The Wairoa and South Dunedin case studies feature in our 2024 report on progress under the National Adaptation Plan - available on our website.

Site visits are important, and so is the kōrero that happens over a cuppa, like this kitchen table meeting with Northland Inc representatives in Hūkerenui. Photo / He Pou a Rangi

Site visits are important, and so is the kōrero that happens over a cuppa, like this kitchen table meeting with Northland Inc representatives in Hūkerenui. Photo / He Pou a Rangi

Keeping it real

Case studies are not just research tools. These are also stories about people and places, full of history and connections to te taiao, the natural environment.

An account like this amplifies people’s lived experience. It shines a spotlight on the everyday – and often increasingly intense – reality for people dealing with the effects of a changing climate.

It also reveals the many ways that adaptation is already, determinedly, underway.

“We know we have adapted before, and will have to adapt into the future – it’s just we don’t know what that looks like.”

OVERVIEW

Innovation in the face of a changing climate

In Te Taitokerau/Northland we heard about a wide range of climate changes, emerging in layered, often overlapping ways – from slow shifts in seasonal patterns to extreme weather events hitting hard and often.

People told us these changes were affecting their coastal and marine areas, rivers, whenua and forests – and the kai systems and livelihoods and communities based on them.

Climate impacts were undermining built and natural systems, and loading new stress on communities already dealing with significant social and economic challenges.

We heard and saw a wide range of innovative responses to these pressures:

- marae installing solar infrastructure and water tanks

- businesses building local solutions to energy supply issues

- communities developing catchment-wide water management

- growers trialling new crops and land practices

- hapū regenerating kai systems using maramataka and mātauranga.

Much of the kōrero focused on the importance of social and community connections as the foundation of climate resilience, and the ways different groups can come together to build strong responses based on local knowledge.

Many of those we met spoke of the potential ahead. We were told that their on-the-ground efforts could grow into the comprehensive response that Te Taitokerau/Northland needs, but they depended on critical inputs from central government.

These three questions are at the heart of the story we heard:

- What lies beneath all the innovative responses we saw in the region?

- What is driving the action – what climate risks are people facing?

- What support do locals want – what helps, what gets in the way?

What we heard on the ground

Primary sector innovation and resilience

Action

Growers are adapting farm practices, and trialling new crops. We heard the warming conditions and the region’s soils and rainfall presented chances for production of new high-value crops. Examples of adaptation to the more variable rainfall patterns include manual pollination to replace bees that cannot fly in the rain, planting on mounds to reduce surface flooding risks and more disease-resistant rootstocks.

Reason

Growers face threats from new pests and diseases, while changes in rainfall and temperature patterns are affecting the fundamentals of horticultural systems. People in the sector told us growing costs and risks require them to adapt quickly, but accessing affordable capital for adaptation projects is difficult.

Patrick Malley, general manager and director of Maungatapere Berries, west of Whangārei, which has made extensive changes in response to climate shifts – and to rebuild from extreme weather events. Photo / AG Images

Action

The pastoral sector is building its ability to respond to climate changes. Farmers are linking up to share knowledge and create stronger community ties – in the wake of extreme weather events there is increased reliance on organisations like Rural Support Trust Te Taitokerau. Since our visit a new Resilient Pastures programme has begun a pilot in the region.

Reason

Grassland farmers are grappling with the dual pressure of rising temperatures and prolonged dry periods affecting pasture quality, and more frequent intense rainfall contributing to pugging and erosion.

Michelle Ruddell on her farm at Ruatangata West, west of Whangārei, where they work hard to improve efficiency despite pasture challenges. Farmers helping farmers through networks like Rural Support makes a lot of sense, she says. Photo / AG Images

Growing resilience in hapori Māori

Action

In the Hokianga, communities are drawing on a history of self-sufficiency to regenerate their food systems and build resilience in the face of rising prices and the pressures of climate change. He Kete Kai Food Security Programme is supported by Far North District Council and Northland Regional Council in a collaborative and equitable model focused on community engagement.

See story about He Kete Kai Food Security Programme

Reason

When extreme weather events happen, these communities can be particularly hard hit. When the region's stretched roading network fails, they lose access to supplies, schools, workplaces, and essential services for prolonged periods.

Food systems researcher Maria Barnes is a key part of the He Kete Kai Food Security Programme, a collective network that uses gardens and fruit orchards to build resilience against climate impacts and ensure a sustainable food supply for Hokianga whānau. Photo / AG Images

Collaborating at a catchment level

Action

Ngātiwai Trust Board and the Whangarei District Council are collaborating on a catchment-wide adaptation project covering a 165-square-kilometre area between Whangaruru and Oakura. This combines deep local knowledge with nature-based solutions to reduce community vulnerability to climate threats.

Reason

These east coast communities face risks of isolation, damage and loss from both coastal and river flooding in severe weather events, declining health of the moana and loss of land and heritage from sea level rise and erosion. This threatens homes, schools, marae, ancestral lands, family farms, kaimoana and cultural heritage including urupā.

Ngātiwai Trust Board Taiao lead, Clive Stone, talks visitors through the layers of a project at Oakura supporting river health and flood management, and a community sports facility. Photo / He Pou a Rangi

Adaptation in a network of rivers and streams

Action

River flood management is a key focus of Northland Regional Council’s climate resilience work. This includes long-running schemes such as on the Awanui River protecting Kaitāia, and recent close work with communities to protect the region’s most at-risk marae.

Reason

We heard that across the region, flooding and poor river health are recurring concerns. Flooding presents widespread risks to transport and other infrastructure, communities and businesses. River health is also under pressure, which strains the natural systems people rely on, and has downstream effects in coastal waters.

Northland Regional Council’s Kaitāia area manager Peter Wiessing takes calls day and night from his community, fielding alerts and questions for the Awanui River scheme that channels water from a 250-square-kilometre catchment through a bottleneck at Kaitāia. Photo / He Pou a Rangi

Keeping connected – the supporting infrastructure

Action

Local companies are investing in resilience measures, alongside their efforts to develop low-emissions energy options. The electricity distributor in the Far North, Top Energy, is focused on strengthening reliability of service to customers through remote network automation and localised generation (including through Ngāwhā Geothermal). Golden Bay Cement, the region's largest industrial employer, is exploring rail as a resilient transport option for the diverted waste products it has used to replace 55 percent of its coal use.

Reason

We heard lost connection from infrastructure failing in extreme weather events threatens business, employment and livelihoods across the region, as well as the safety of households and communities. Transport, power, telecommunications and digital networks and water systems were all described as fragile.

Powerlines straddle a hillside near the south Hokianga Harbour. The fragility of Te Taitokerau/Northland's energy infrastructure is a major concern, especially in isolated areas that have experienced repeated disruption. Photo / AG Images

BACKground

Te Taitokerau/Northland's changing climate

The technical report underlying the 2022 Te Taitokerau Climate Adaptation Strategy includes this summary of climate change impacts and implications for the region.

“Te Taitokerau is likely to experience physical impacts from climate change such as increases in coastal inundation and erosion, more regular river flooding and sedimentation, extended periodic dry periods, increased fire danger weather, and alterations to seasonal weather conditions such as frosts and spring rainfall decline. These will increasingly create implications for our region, by disrupting our water, land and ecosystems, our people, culture and economy, and will fundamentally influence the way local government provides services to the community.”

More recent reports and projections that cover the region reinforce this.

The Government’s state of our atmosphere and climate report published in 2023 shows there are already more frequent and intense weather events, and that rainfall annual patterns have changed, average air temperatures have risen, and the number of days where frost will form have reduced.

Looking ahead, the latest climate projections, published by the Ministry for the Environment in 2023, show that average temperatures are likely to rise across the region, with greatest seasonal change projected in summer. Frosts are expected to become rare events, and hot days more common. Rainfall patterns are expected to become more uneven. Although total annual rainfall might drop – particularly in spring, by up to 25 percent – the kind of heavy downpours that can increase flood risk will still happen.

Te Rarawa project manager Paul Hansen and the Commission's Chief Science Advisor Grant Blackwell look out over Tupehau reservoir north of Kaitāia on Te Rarawa whenua. Photo / He Pou a Rangi

Te Rarawa project manager Paul Hansen and the Commission's Chief Science Advisor Grant Blackwell look out over Tupehau reservoir north of Kaitāia on Te Rarawa whenua. Photo / He Pou a Rangi

Longer dry spells will reduce soil moisture, limit pasture growth, and raise the risk of seasonal water shortages. Droughts are projected to become more frequent and last longer, particularly on the east and west coasts, and southern inland area. This brings with it the risk of wildfire, particularly for communities living near forests.

Higher average sea levels, which projections show could rise by up to 60 cm by 2080 and potentially 1.5 metres by 2130, pose significant challenges for Te Taitokerau/Northland’s extensive coastline. Climate change impacts on the moana also include the effects of warming seas and ocean acidification, and increase in non-native marine species, as set out in the 2025 state of our marine environment report.

Who gets hit harder by climate change?

In any area, some groups in the population are more likely to be affected by the impacts of climate change. This can be a result of where they live and work (for example in rural areas where most jobs are in climate-sensitive industries like farming and forestry). It can also be because they are more likely to be physically affected – for instance children, older people, and people with disabilities or chronic health conditions.

Recent analysis by Environmental Health Intelligence New Zealand provides a view of what can make people more 'socially vulnerable' to climate and natural hazards. Northland Region stands out on some measures, including access to money to cope with crises, access to the internet, and safe, healthy and uncrowded households.

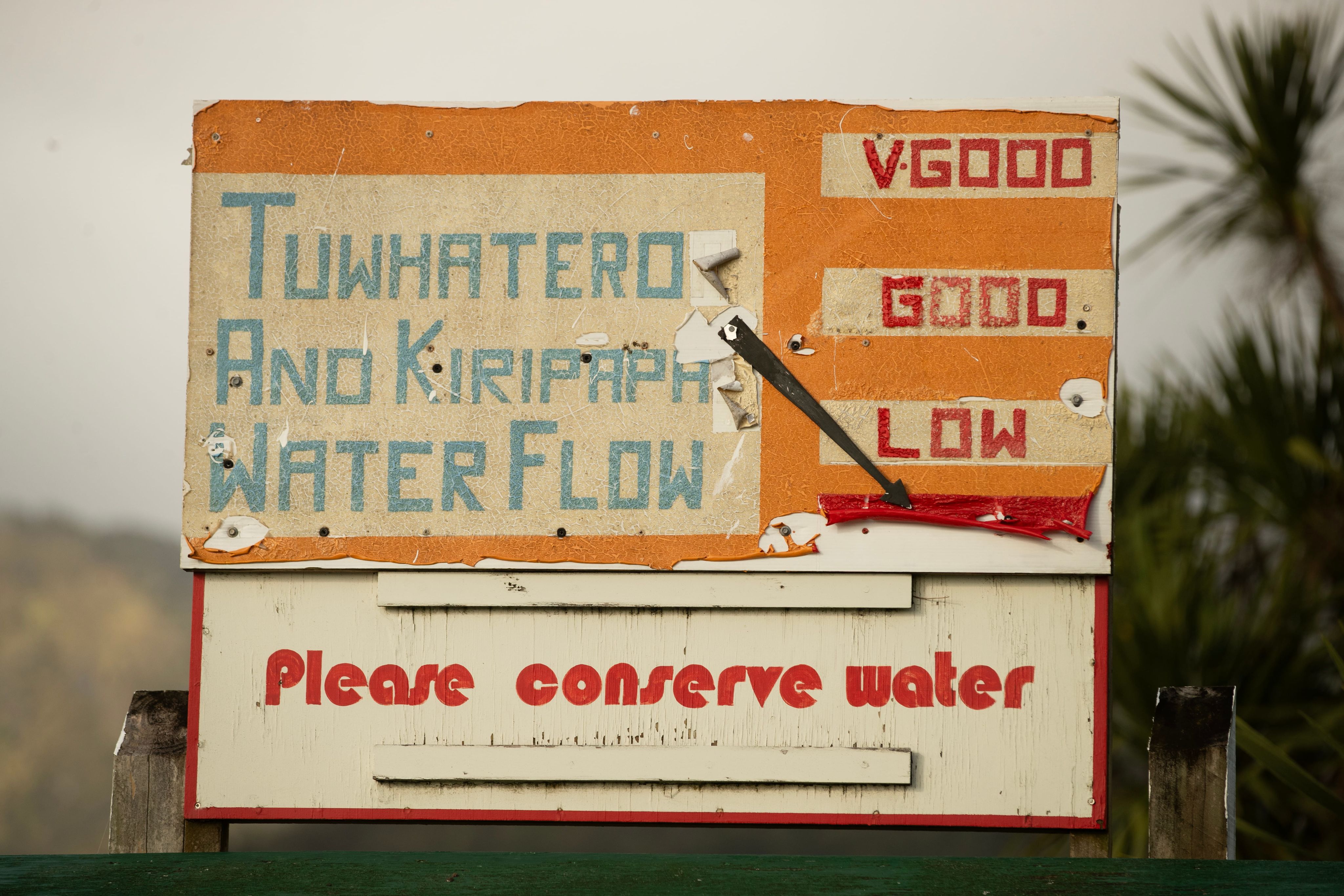

Signs like this one in Whirinaki, in the south Hokianga, underscore the daily challenges communities face. Photo / AG Images

Signs like this one in Whirinaki, in the south Hokianga, underscore the daily challenges communities face. Photo / AG Images

These less visible factors influence how people experience climate change, and can mean some people have very limited options to avoid negative impacts of climate change. They can get left behind as others adapt.

In Te Taitokerau/Northland we heard how climate impacts are loading on top of existing socio-economic pressures. This applied across the board, and was a particular issue for rural Māori communities. Finding ways to make sure all communities in the region were able to cope with the effects of a changing climate and to build their resilience was a critical issue for many we talked to.

“It doesn't matter where we're from, we all actually want the same things: we want food security, water security and a safe roof over our head.

Zonya Wherry, Hokianga community consultant. Photo / supplied

Zonya Wherry, Hokianga community consultant. Photo / supplied

What people said they need to succeed

Practical approaches, connections and systems

Across all our conversations in Te Taitokerau/Northland, we heard these calls – for support and for action by Government.

Government support for:

- Approaches to adapting to climate change that help all to cope and build resilience

- Responses that are founded on community strengths and values

- Opportunity to lead local adaptation action in ways that weave in broader goals

- Collaborative partnerships that help connect across communities and sectors

Government action in these areas:

- Reliable access to information and data, resources and technical support

- Long-term policy and funding pathways, including support to access capital

- Greater clarity about roles and responsibilities in legislation and national plans

- Investment in infrastructure to keep people connected and safe.

This case study and our 2026 reports

Our case study report does not compare what people told us in the region with the adaptation action that the Government is already taking, including under the National Adaptation Framework published in October 2025.

That will be the focus of our 2026 reports, particularly the second monitoring report on progress made under the Government’s national adaptation plan.

The stories we heard in Te Taitokerau/Northland reflect locals’ recent experience of changes in their climate, and their understanding of risks in the near future.

Case studies provide a close view: what is happening in one area, at this time. Our 2026 adaptation reports will take the longer view – that the country can use to assess what national action is needed now to prepare for the future.

Those reports will be based on analysis of a wide range of evidence, including projections for climate change over the rest of the century.

Visit the Commission website for more info about our 2026 adaptation reports:

- the second national climate change risk assessment

- our second monitoring report on progress on the Government’s national adaptation plan.

Published: December 2025

© Crown Copyright

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY-NC-ND) licence. The work can be downloaded, copied or distributed in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for non-commercial purposes only, and only if attributed to the Climate Change Commission.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

For images that include people: Out of respect for the people photographed, we ask that these images only be used in the context of this case study.